Victoria Reifler Bricker, Ph.D., is an esteemed American anthropologist and ethnologist, widely recognized as one of the leading scholars in Mesoamerican studies. She is best known for her groundbreaking research into both contemporary and historical Maya language and culture.

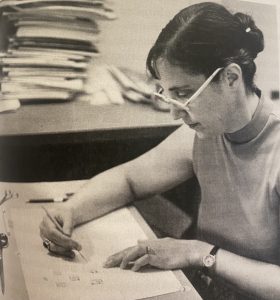

Surrounded by her books and art gathered from her travels, Bricker radiates enthusiasm for her life’s work. Her eyes sparkle as she recounts her numerous discoveries and cultural knowledge she learned from the Maya people. Her lovely smile reflects a quiet pride in all she has accomplished as well as her shared experience with so many of her distinguished colleagues. Her distinctive white glasses, which she’s worn since high school, have become her signature look.

As she reflected, her life “has been punctuated by a series of journeys, and everything is tied together in an intricate web.” Indeed, Bricker has a remarkable ability to follow each thread of her journey to its end, embracing opportunities and discoveries along the way.

This sentiment echoes Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s insight: “All mankind is tied together; all life is interrelated, and we are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of identity.” Bricker’s life embodies this interconnectedness, as chronicled in her 2017 memoir, Transformational Journeys: An Ethnologist’s Memoir.

An example of how everything is tied together was in 1988, on a Caribbean cruise, where Bricker was a lecturer to her fellow travelers. A woman who heard her lecture commented that Bricker reminded her of a professor she once knew—turns out that professor was actually Bricker’s father. It was one of those moments Bricker truly realized “how connected we are in the world.”

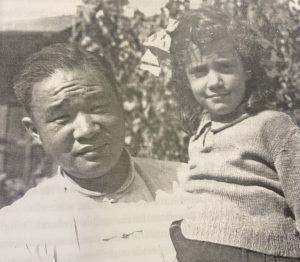

A Childhood Marked by War and Adaptation

Born in Hong Kong in 1940, Bricker and her family soon relocated to Shanghai. During World War II, after the Japanese occupation of the city, she, her British mother and her brother were placed in a Japanese internment camp. These camps were established in retaliation for the U.S. internment of Japanese American citizens in California and Nevada. Thankfully, their time in the camp lasted just over a year; her Austrian father, considered a neutral party, was not interned. The family stayed in Shanghai for two additional years before relocating to the United States, where her father accepted a position as an associate professor of Chinese in the Far Eastern Department at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Bricker recalls little of her early childhood but vividly remembers the fear during American bombing raids and the sound of explosions—a memory that still makes fireworks unsettling for her. In high school, when a teacher proudly recounted his involvement in those air raids, Bricker courageously confronted him: “You dropped the bombs on me.” According to her younger sister, who later took the same course from him, he never mentioned of it again.

Academic Roots and Linguistic Talent

Bricker credits her father, Erwin Reifler—a distinguished professor of languages—for her facility with language. She speaks five languages besides English: Spanish, French, German, Tzotzil and Yucatecan Maya. Her father believed in memorizing texts for language learning—a method she embraced while learning German, after seeing his success with 13 different languages.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and humanities from Stanford, she pursued a master’s and doctorate in anthropology at Harvard. It was there that she met her future archeologist husband, Harvey Bricker, during a cultural anthropology class. She admired his intellect and oral delivery, and though early in their marriage they often lived on different continents for their research, they remained deeply connected personally and professionally.

Life’s Work with the Maya

Bricker’s academic career flourished at Tulane University, where she is now professor emerita. She authored 10 books, four of which were co-authored, including Astronomy in the Maya Codices, which she and Harvey worked on for 10 years. The book received the John Frederick Lewis Award from the American Philosophical Society.

She also co-authored A Dictionary of the Maya Language, as Spoken in Hocabá, Yucatán—the only existing Maya-English dictionary. Her principal collaborator, Eleuterio “Elut” Po’ot Yah, had two Maya surnames, which Bricker believed indicated a purer linguistic lineage, minimizing Spanish influence on the work. They labored over the dictionary for 16 years between other academic duties. Elut’s wife, Ofelia Dzul de Po’ot, contributed plant names and their uses for the dictionary.

Immersive Fieldwork and the Study of Humor

Her interest in Maya culture and everyday life began at Harvard when she learned of research being conducted in the Tzotzil region of southern Mexico. Bricker was struck by the warmth of the Tzotzil people, sparking her long-term ethnographic commitment. Tzotzil, one of 20 distinct Maya languages, had no written form—so she learned it entirely by ear.

Her first book, Ritual Humor in Highland Chiapas, focused on humor in religious contexts, editions of which were also published in Spanish and Japanese, which provide a unique lens for anthropological study. She developed structured questions and recorded multiple ceremonies across the region, making sure to engage in social interaction with each native speaker. Because the ceremonies relied on the oral tradition within each of the indigenous communities, to gain a deeper understanding she including taking detailed notes and audio recordings to better understand and preserve the cultural practices. What began as an intellectual journal evolved into a series of influential publications which shared the cultural nuances of the Maya people and provided a unique tool for future learners.

From Grammar to the Stars: The Journey to Hieroglyphs

Bricker’s expertise in Maya grammar, gained through teaching Tzotzil and Yucatecan Maya, paved the way for her future work in deciphering hieroglyphs. Harvey encouraged her to pursue this field further by gifting her books on Maya glyphs. Ultimately, she realized she had to learn the written language to be taken seriously as a scholar. As she put it, “One thing led to the another.”

Her linguistic research led to the study of reading order in Maya codices and, eventually, the astronomical content embedded within them. This expanded into collaborative teaching and research on Maya astronomy with Harvey, culminating in their award-winning book.

In 2002, Bricker was elected to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, a recognition of her lifetime contributions to anthropology and Mesoamerican studies.

Later Life and Continued Scholarship

Now residing at Oak Hammock at the University of Florida, a continuing care retirement community in Gainesville, Florida, Bricker continues her research in collaboration with former students and colleagues. Recently she published a paper co-authored with two colleagues bearing the title: Maya Astronomy and the Procession of the Equinoxes.

When asked about her favorite place to live, Bricker—who has lived in China, Germany, France, Mexico, and the U.S.—chose Mexico. “So much of my life was focused on learning about the cultural identity, diverse perspectives and history of the people,” she explained.

She speaks fondly of life at Oak Hammock, praising the diversity of residents and the connections she has made with people from around the world. She also enjoys conversations with the multilingual staff.

Victoria and Harvey Bricker enjoyed 52 years of marriage and scholarly partnership until he passed away in 2017. She notes that his keen geographic sensibilities helped ground her work in space and context. Together, they built a body of research from their scientific discovery that continues to inspire scholars and future generations.

Bricker hasn’t set any long-term goals for now but continues to work on her Maya scholarship which has dominated her life-long career and passion.